Cultivating Resilience through Local Art and Culture

In East Africa and the Horn, mental health support is crucial in impoverished and violent communities. However, therapy may be unaffordable, unavailable, or not culturally desired.

GSN provides culturally grounded solutions by utilizing art and culture to promote community mental health prevention.

Healing is what makes peace work. The healing process is contextualized and based on our culture. Thus, we invest heavily on contextualizing our curriculum to local needs and realities.

GSN's origins can be traced back to a clan conflict in the Mandera triangle between the Murle and Garre in 2008. The larger network was engaged in cross-border peacebuilding work at the time, and in response to the conflict, they offered a three-day "trauma-healing" workshop for 40 religious leaders, nurses, and teachers. The participants were able to apply what they had learned in practical ways making a significant impact on the local peacebuilding process. This experience made us realize we needed to design something new that would allow people to move from merely surviving to thrive, and in a way heavily grounded in an easy-to-understand, contextualized approach.

The Green String Network, therefore, is committed to continuously evolving its curriculum and approach to promoting mental health and well-being among young people in East Africa and the Horn. Through our flagship framework, Well-being and Resilience (WebR), GSN has been able to work with community-based organizations in Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Ethiopia to help people articulate their experiences of trauma and recognize how these experiences have shaped them.

When implementing healing-centered programs in new contexts, it is important to adapt the curriculum and design new materials for these contexts so that the new program speaks to the realities, experiences, and uniqueness of the people and communities that will use the program materials.

Our collection of over 1,500 specially commissioned watercolor paintings from regional artists serves as a testament to the transformative power of our approach being rooted in local culture and art, and highlights the importance of investing in mental health and well-being as a means of building healthy, resilient, and sustainable communities.

The Principles of Adaptation

Inclusion

Adapting a program to a specific context requires involving the intended recipients in the process. It is important to take note of who is not included and to inquire about their absence. Including minority groups can provide a different perspective and raise important issues that may not be considered by dominant groups. Diverse stakeholders provide insight, critical information, and feedback that ensures the adapted materials are relevant to the target population.

Cultural Sensitivity & Contextual Relevance

Adapted materials must respect cultural beliefs, practices, norms, and traditions, and be relevant to the context in which they are used. Different groups may require different approaches, with some benefiting from academic methods, others from storytelling and the arts, and many from a mix of approaches.

Cultural Sensitivity & Contextual Relevance

Adapted materials must respect cultural beliefs, practices, norms, and traditions, and be relevant to the context in which they are used. Different groups may require different approaches, with some benefiting from academic methods, others from storytelling and the arts, and many from a mix of approaches.

Indigenous Storytelling for Cultural Heritage and Healing

Stories are effective tools for communication and expression, often more persuasive than data and facts alone. They take listeners on a journey, shifting their perspectives, and are remembered up to 22 times more than facts alone. However, stories can also spread hate and fear, poisoning nations. As Nigerian poet Ben Okri notes, "A people are as healthy and confident as the stories they tell themselves." By incorporating personal stories and experiences into program materials, individuals are more likely to accept the message being conveyed, supporting their own healing agenda.

Continuous Learning

Learning from the communities we serve is crucial for the successful adaptation and effective use of program materials. Integrating effective practices from different cultures and contexts improves the material being adapted and lays the groundwork for future adaptations. As time passes, new issues may emerge that may require adaptation of the process, such as the shift to virtual processes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, emerging approaches and academic research may offer valuable insights that can be integrated into the curriculum, enhancing the work being done.

Integration

Integrating information from previous interventions with what is learned when adapting materials to a new context is important for the continuous improvement of the programs we implement - this is both in content and in impact.

The Name and Look: A Cultural Symbol

During the adaption process, workshop participants collaborate to create a name and tagline that reflects their healing process, as well as brainstorm symbols significant to them and their community. With the name agreed upon, the adaptation team works with a designer, artists, and key participants to develop the logo and all images that are used on the program. Bringing in local artists to collaborate with the adaption team allows them to better understand the vision and goals of the project and to visually capture the details through watercolor illustrations and paintings. Having artists in the room helps to expedite the logo design, painting of watercolour images, and merge the group's various ideas and themes in all visual elements.

For example, in the Abyei adaptation process, the participants decided on the name ‘Arise and Shine’ after internal conversations. They decided on the name in Dinka first, then translated it into Arabic, then English. The large mango tree, which is a sight everyone in Abyei is familiar with, was sketched by an artist and the nine stars around the tree in the sky were proposed to represent the nine Dinka Agok clans from Abyei.

The Elements of Adaptation

The Cycles of Violence

As part of the adaptation process, workshop participants also explore different elements of the cycles of violence, including both "hurting-self/acting in" and "hurting-others/acting out," which provide a context for exploring and understanding everyday mental health issues. This list of issues can help participants recognize distress and mental health concerns in themselves and in others in their community.

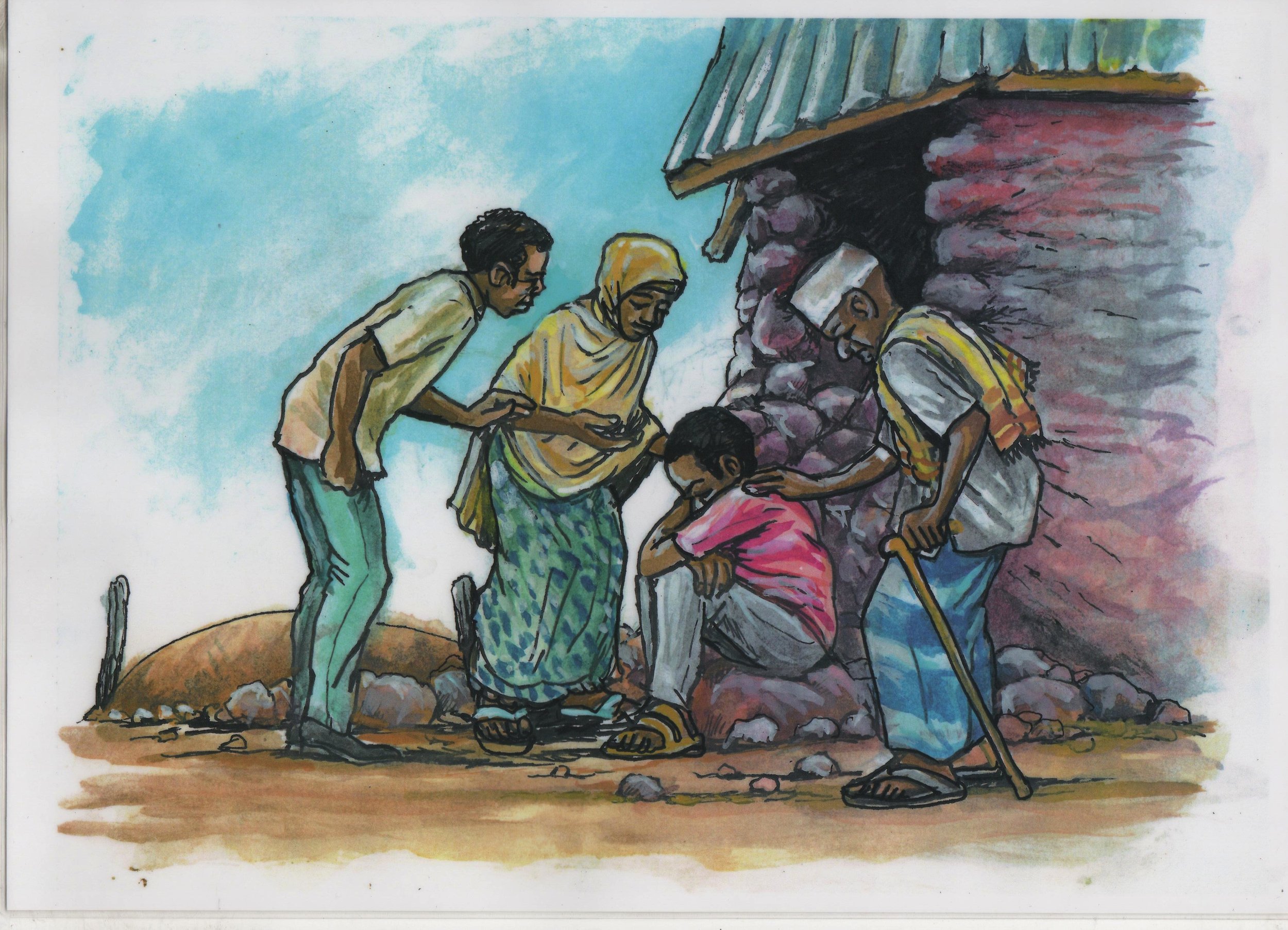

Through individual brainstorming, participants identify and group the different ways people hurt themselves and others. The group then ranks and prioritizes these issues, giving space to lived experiences and observations of others in their daily lives. his process is also applied to the "breaking free" element, which is categorized by truth-telling, forgiveness, justice, peace, and reconciliation. This approach allows participants to understand and address the root causes of violence, trauma, and emotional distress in their lives and communities.

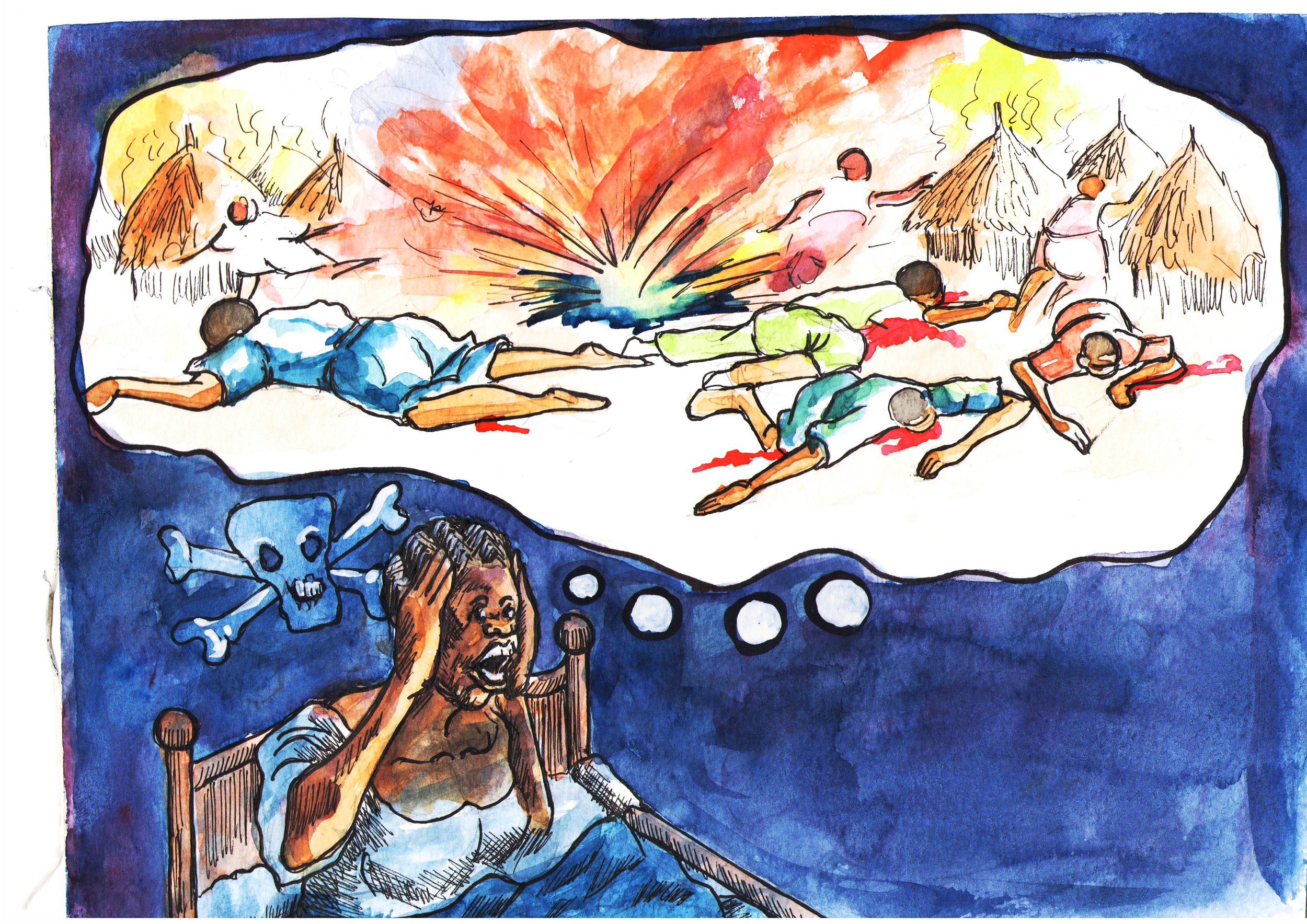

In the visual elements of the programs, lots of watercolor paintings are used, many of which depict violent scenes. Participants in the adaptation process recognize that some visual images can be emotionally difficult due to the subject matter they depict. However, they believe that including such images is important to document the harsh realities of people's lived experiences and to facilitate the truth-telling process. They note that these images are not re-traumatizing, but instead play an important role in the healing process. Despite being uncomfortable, participants insist that difficult images are necessary to convey the stories in people's hearts. This helps to showcase the everyday actions that people take to support their emotional and mental well-being and to promote a more balanced and positive view of the community.

In South Sudan, for example, newspapers and social media are the main sources of images for people, but they often depict violence, destruction, and pain, leaving little room for positive imagery. To counter this narrative and promote a healing-centered approach, it was deemed important to highlight the positive and healthy practices that exist within society during the Arise and Shine adaptation process. This helps to showcase the everyday actions that people take to support their emotional and mental well-being and to promote a more balanced and positive view of the community.

Truth Telling in the Adaptation Process

Our Journey of Adaptation

A new approach to collective healing

Quraca Nabadda’ is Somali for the Acacia tree, or ‘the tree of peace’. Somalis have sat together under this tree to talk, laugh, cry and celebrate for centuries. It is also the tree under which Somalis have traditionally met to resolve disputes.

The use of watercolor paintings used on the programme enhanced the healing process and allowed people to see themselves and their lived experiences. Through artist Alif's engaging illustrations, the cycle of violence was made culturally relevant. The paintings were made into flashcards, and participants told the stories they saw in the paintings, making the cycle of violence come alive in the storytelling that takes place in the safe space of the groups.

Healing brings a New Dawn

The Kumekucha adaptation in 2017 stands out as the first time we co-created the materials alongside community members themselves. Through the use of paintings, we have supported volunteer Circle Keepers in their mission to cultivate resilience and foster hope in communities that may otherwise feel a sense of hopelessness.

Reimagining healing takes effort, time, and resources, but it's an investment worth making. Empowering individuals with tools to own their own healing journeys is crucial. The paintings provide a platform for highlighting lived experiences of people who have gone through challenging circumstances. Each painting captures diverse emotions and experiences, and each viewer sees something unique based on their life experiences. This approach to storytelling enables people to explore their experiences without disclosing all their secrets until they are ready.

We are the experts of our own lives

Two years later, we then worked with South Sudanese religious leaders to develop the Morning Star initiative in 10 languages. Somali Artist Alif went to Juba to work with five South Sudanese artists. The paintings inspired hope in a country that is weary of war and violence.

From Morning Star, we learned that people must own their own healing agenda, and when local and indigenous knowledge and rituals are a part of the healing processes healing becomes possible. The paintings made the process assessible.

Hearing your adversary's story can lead to healing

Muamko Mypa: Healing the Uniform examines the cycle of violence, trauma, resilience, and healing for police officers. Through a co-design process involving police and prison officers, artists, and community members, including those who had been harmed in the past by the security sector, the artwork was developed that helped with the healing process.

Co-designing empowers and healing

Kumekucha Quest uses music, storytelling, and the arts as mediums for emotional regulation and for helping people cope with emotional distress. The design of the program logo was done by young people, including the artist who was part of the design and adaptation workshop.

Instead of telling people to be resilient, we must create environments where resilience is possible, if not inevitable.

Artists on the frontline

Watercolor paintings are a significant part of the adaptation process. The artists and illustrators paint their interpretations of the stories and definitions generated from the adaptation workshop, providing emotional depth that graphic and computer-generated artwork often lacks. Involving artists in the adaptation workshop is critical to the success of the project.

Women Artists

In Africa, the involvement of women artists is especially important, as they bring a unique perspective that is often missing. However, it can be challenging to find women artists in many African countries. In South Sudan, for example, there were no women artists in 2015, and the lead artist spent five years training them to be able to contribute to renewed process. Involving women artists is critical to ensuring that the adaptations are culturally appropriate and inclusive.